The Geographical Society of Paris organized a committee in 1876 to seek international cooperation for studies to fill in gaps in the geographical knowledge of the Central American area for the purpose of building an interoceanic canal. The committee, a limited company, La Société Civile Internationale du Canal Interocéanique de Darien, was headed by Ferdinand de Lesseps. Exploration of the Isthmus was assigned to French Navy Lieutenant Lucien N. B. Wyse, a grandson of Lucien Bonaparte. Armand Réclus, also a naval lieutenant, was his chief assistant.

After exploring several routes in the Darien-Atrato regions, Wyse returned to Paris in April 1877. De Lesseps, however, rejected all of these plans because they contained the construction of tunnels and locks. On a second Isthmian exploratory visit beginning December 6, 1877, Wyse explored two routes in Panama, the San Blas route and a route from Limon Bay to Panama City, the current Canal route. In selecting the latter, his plan was to construct a sea level canal. The route would closely parallel the Panama Railroad and require a 7,720-meter-long tunnel through the Continental Divide at Culebra.

With this plan for a Panama canal, Wyse traveled to Bogota, where, in the name of the society, he negotiated a treaty with the Colombian government. The treaty, signed on March 20, 1878, became known as the Wyse Concession. It granted exclusive right to the Société Civile to build an interoceanic canal through Panama. As a provision of the treaty, the waterway would revert to the Colombian government after 99 years without compensation.

A congress, the Congrès International d’Etudes du Canal Interocéanique (International Congress for Study of an Interoceanic Canal) was planned to take place in Paris on May 15, 1879, with invitations sent out by the Société de Géographie (Geographical Society) of Paris. Critics claimed that a principal purpose of the congress was to give needed legitimacy to the Wyse Concession, legitimacy greatly needed, as recognized by de Lesseps, to bring in financial backing. The purpose of the congress was not to approve a route or a plan, that decision had already been made by de Lesseps, but to give that decision and the already negotiated Wyse Concession a public introduction and ceremonial sendoff. It also served to provide the appearance of impartial international scientific approval.

Fourteen proposals for sea level canals at Panama were presented before the congress, including the de Lesseps plan of Wyse and Réclus. A subcommittee reduced the choices to two — Nicaragua and Panama.

As might be expected, engineers and others offered differing opinions concerning the various plans. One such engineer was Baron Godin de Lépinay (Nicholas-Joseph-Adolphe Godin de Lépinay, Baron de Brusly). The chief engineer for the French Department of Bridges and Highways, Lépinay was known for his intelligence, as well as his condescending attitude towards those with whom he did not agree. He was the only one among the French delegation with any construction experience in the tropics, 1862 construction in Mexico of a railroad between Cordoba and Veracruz. At the congress, he made a forceful presentation in favor of a lock canal.

The de Lépinay plan included building dams, one across the Chagres River near its mouth on the Atlantic and another on the Rio Grande near the Pacific. The approximately 80-foot height of the artificial lake thus created would be accessed by locks. The principal advantages of the plan would be the reduction in the amount of digging that would have to be done and the elimination of flood danger from the Chagres. Estimated construction time was six years. Since this plan required less digging, there would be, according to prevailing theories that tropical diseases were caused by some sort of toxic emanations coming from freshly dug earth being exposed to the air, less such problems. The de Lépinay design contained all of the basic elements ultimately designed into the current Panama Canal. The French company would use these concepts as a basis for the lock canal they would eventually adopt in 1887 following the failure of their sea level attempt. Had this plan been originally approved, France might well have prevailed in their canal construction effort. Had it been adopted at the beginning, in 1879, the Panama Canal might well have been completed by the French instead of by the United States. As it was, however, the de Lépinay design received no serious attention.

The American delegation’s Nicaragua plan was introduced by Aniceto García Menocal. Cuban by birth, Menocal was a civilian engineer assigned to the Grant surveys in Nicaragua and Panama by Admiral Ammen. The well organized and persuasive presentation by the Americans very nearly upset de Lesseps’ carefully orchestrated plans. But, again, this was not to be.

De Lesseps thought a week enough time to gain consensus and wrap up the details. With things now threatening to get out of hand, he, on Friday, May 23, “threw off the mantle of indifference,” as one delegate wrote, and convened a general session. Striding confidently in front of a large map, a relaxed de Lesseps addressed the congress for the first time. He spoke spontaneously, in simple, direct language, and with great conviction, if not abundant knowledge, making everything sound right and reasonable. The map, which he referred to with easy familiarity, clearly showed that the one best route was through Panama. It was the route that had already been selected to develop Panama’s transcontinental railroad. There was no question that a sea level canal was the correct type of canal to build and no question at all that Panama was the best and only place to build it. Any problems – and, of course, there would be some – would resolve themselves, as they had at Suez. His audience was enthralled.

Following the speech, everything fell into place for the de Lesseps camp, and the building of a sea level canal through Panama was the recommendation of the Technical Committee. By no means, however, was everything peaceful and unanimous. Before the vote was even taken nearly half the Committee, walked out. Following the vote, with the full congress reconvened, the Committee report was read and the final, historical vote cast. The Committee resolution read:

“The congress believes that the excavation of an interoceanic canal at sea-level, so desirable in the interests of commerce and navigation, is feasible; and that, in order to take advantage of the indispensable facilities for access and operation which a channel of this kind must offer above all, this canal should extend from the Gulf of Limon to the Bay of Panama.”4

The resolution passed with 74 in favor and 8 opposed. The “no” votes included de Lépinay and Alexandre Gustave Eiffel. Thirty-eight Committee members were absent and 16, including Ammen and Menocal, abstained. The predominantly French “yea” votes did not include any of the five delegates from the French Society of Engineers. Of the 74 voting in favor, only 19 were engineers and of those, only one, Pedro Sosa of Panama, had ever been in Central America.

Following organization on August 17, 1879, of the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique de Panama, with de Lesseps as president, the Wyse Concession was acquired from the Société Civile. A new survey was ordered and an International Technical Commission of well-known engineers went to Panama, accompanied by de Lesseps, to get a first-hand look at the Isthmus.

Making good on his promise to dig the first spade of earth for the Panama Canal on January 1, 1880, de Lesseps organized a special ceremony at which his young daughter, Ferdinand de Lesseps, would do the honors of turning the first sod. The ceremonial act was to take place at the mouth of the Rio Grande, scheduled to become the Pacific entrance to the future canal.

On the designated day, but later than the designated time, the steam tender Taboguilla took de Lesseps and a party of distinguished guests three miles to the site on the Rio Grande where the ceremony would take place, following appropriate feasting and festivities on board. However, since late guests had delayed the Taboguilla, the Pacific Ocean tide had receded such that the vessel could not land at the designated site. The undaunted de Lesseps was, of course, ready with a solution. He had brought a special shovel and pickaxe with him from France especially for the occasion. Now, declaring that the act was only symbolic anyway, he arranged for his daughter Ferdinande to strike the ceremonial pickaxe blow in a dirt-filled champagne box. The empty champagne box is, perhaps, a clue to the gaiety and applause that followed the official act.

De Lesseps then decided that another ceremony should inaugurate the section of the canal that would have the deepest excavation, the cut through the Continental Divide at Culebra. A ceremony was arranged, and on January 10, 1880, appropriate officials and guests gathered at Cerro Culebra (later known as Gold Hill) for the ceremony, which included witnessing the blast from an explosive charge set to break up a basalt formation just below the summit. After blessings by the local bishop, young Ferdinande again performed the honors, pushing the button of the electric detonator that set off the charge that hurled a highly satisfactory amount of rock and dirt into the air.

As de Lesseps was a trained diplomat and not an engineer, a fact that he should perhaps have more often remembered during canal design decisions, his son Charles took on the task of supervising the daily work. De Lesseps himself handled the important work of promoting and raising money for the project from private subscription. Not having the least scientific or technical bent, de Lesseps relied upon a rather naive faith in the serendipitous nature of emerging technology. Thus he worried little about the problems facing this gigantic undertaking, feeling sure that the right people with the right ideas and the right machines would somehow miraculously appear at the right time and take care of them. His boundless confidence and enthusiasm for the project and his consummate faith in the miracles of technology attracted stockholders.

In the meantime, the International Technical Commission set about the difficult task of exploring and charting the canal route. Between Colon and Panama City, the canal line was divided into sections, each section in charge of a team of engineers. Survey findings were compiled into a final report by the commission headquarters in Panama City.

The International Technical Commission was required to verify all previous surveys, including those done by Wyse and Réclus and the U.S. studies of Lull and Menocal. The ultimate goal was to determine the final line of the canal leading to the preparation of design specifications and working plans. Another goal was to convince investors that de Lesseps was not just the promoter for a hastily conceived, half understood, imperfectly planned project that, most likely reflected unreliable cost estimates.

However, the few weeks’ time allowed for this survey work was far too short for an investigation of such importance. Owing to this fact, the content of the technical commission’s report, submitted on February 14, 1880, was scientifically and professionally thin. In fact, it comprised little more than a rubber stamp for the project as conceived by de Lesseps. In approving a sea level canal, the commission reported no significant construction difficulty in cutting the deep channel through the Continental Divide at Culebra Cut and estimated that construction would take approximately eight years. The recommendations also included a protective breakwater at Limon Bay and a possible Pacific-side tidal lock.

To do the work, de Lesseps contracted Couvreux and Hersent, with whom he had worked at Suez. Looking at the work in retrospect, it can be seen as falling into four phases. During the first phase, from March 12, 1881, to the end of 1882, the entire project was under Couvreux and Hersent. During the second phase, 1883 through 1885, following the withdrawal of Couvreux and Hersent, the work was accomplished by a number of small contractors under supervision of the company itself. The third phase, between 1886 and 1887, saw the work done by a few large contractors. Finally, in the fourth phase, beginning in 1888, the sea level project was finally, though temporarily, abandoned for a lock canal with the idea that, after the lock canal was functional, the channel could be deepened gradually to make a sea level canal. But it was already too late, and the work gradually ground to a halt. Armand Réclus, the Agent Général or chief superintendent of the Compagnie Universelle, led the first French construction group of about 40 engineers and officials. They landed at Colon on January 29, 1881, aboard the Lafayette. An optimistic Réclus expected preparatory tasks to take about a year, but Panama’s sparse population did not lend itself to labor recruitment, nor did its thick jungles lend themselves to quick movement through the countryside to accomplish the work. Gaston Blanchet, Couvreux and Hersent’s director, accompanied Réclus to the Isthmus. As Blanchet was known to be the company’s driving force, it was a terrible blow when, just 10 months into the project, he died, apparently of malaria.

Work went forward, however. Surveys were completed and the canal line more accurately determined. Construction was begun on service buildings and housing for laborers. The delivery of machinery was expected soon. Some was manufactured in Europe and some in the United States. All manner of equipment was needed, from launches, excavators, dump cars and cranes to telegraph and telephone equipment.

De Lesseps was aware that the railroad was important to the work, and control of this vital element was gained by the French in August 1881. But it cost them dearly, more than $25,000,000 — about a third of Compagnie Universelle resources. Strangely, however, the railroad was never organized to serve anywhere near its full potential, especially in moving material from the site of excavation to deposit areas.

As the work force increased, so did illness and death. The first yellow fever death among the 1,039 employees occurred June 1881 soon after beginning of the wet season. A young engineer named Etienne died on July 25, supposedly of “brain fever.” A few days later, on July 28, Henri Bionne died. Holding degrees in medicine and law, as well as an international finance authority, he was a significant player in the Paris operation. In his book, “The Path Between the Seas, David McCullough wrote: “The cause of death would be attributed in Paris to ‘complications in the region of the kidneys.’ But on the Isthmus, the story would be told for as long as the French remained. He had arrived from France to make a personal inspection for de Lesseps, and several of the engineers had arranged a dinner in his honor at the employees’ dining hall at the camp at Gamboa. It was a festive evening apparently. Bionne, the last to arrive, had come into the hall just as everyone was being seated. One of the guests, a Norwegian woman, was exclaiming with great agitation that there were only thirteen at the table. ‘Be assured, madame, in such a case it is the last to arrive who pays for all,’ Bionne said gaily. ‘He drank to our success on the isthmus,’ one engineer recalled; ‘we drank to his good luck…’ Two weeks later, on his way home to France, Bionne died of what the ship’s doctor designated only as fever, not yellow fever. The body was buried at sea.”

By October, equipment and materials were arriving and accumulating in Colon faster than a work force could be hired to use them. By December 1881, the French had set up headquarters in Panama City at the Grand Hotel on Cathedral Plaza.

A banquet and ball in Panama City marked the official beginning of Culebra Cut excavation on January 20, 1882. However, little actual digging was accomplished because of lack of organization in the field. Engineers continued doing survey and preliminary work, work necessary to the project considering the skimpy studies originally done, and sending reports to Paris.

On the Isthmus, the Compagnie Universelle established medical services presided over ty the Sisters of St. Vincent de Paul. The first 200-bed hospital was established in Colon in March 1882. On the Pacific side, construction for L’Hôpital Central de Panama, the forerunner of Ancon Hospital, was begun on Ancon Hill. It was dedicated six months later, on September 17, 1882. With the information on the mosquito connection in the transmission of yellow fever and malaria not yet discovered, the French and the good sisters unwittingly committed a number of errors that were to cost dearly in human life and suffering. The hospital grounds were set out with many varieties of vegetables and flowers. To protect them from leaf-eating ants, waterways were constructed around flowerbeds. Inside the hospital itself, water pans were placed under bedposts to keep of insects. Both insect-fighting methods provided excellent and convenient breeding sites for the Stegomyia fasciata and Anopheles mosquitoes, carriers of yellow fever and malaria. Many patients who came to the hospital for other reasons often fell ill with these diseases after their arrival. It got to the point where people avoided the hospital whenever possible.

Finally, with all excavating arrangements made, Couvreux and Hersent decided to withdraw from the project and wrote to de Lesseps requesting cancellation of their contract on December 31, 1882.

For a time, confusion reigned, until appointment of Jules Dingler as the new Director General. An engineer of outstanding ability, reputation and experience, Dingler was unphased by the yellow fever threat, and, accompanied by his family, arrived in Colon on March 1, 1883, along with Charles de Lesseps.

Dingler concentrated on restoring order to the work and the organization; however, in doing so, he incurred no small amount of dislike. At this time a new system, the system of small contracts, was initiated and nearly thirty were granted. For these contracts, the Compagnie Universelle rented out the necessary equipment at low rates. It wasn’t particularly efficient, requiring a great deal of paperwork and involving numerous lawsuits in Colombian courts, but the work was getting done, making use of the available labor force.

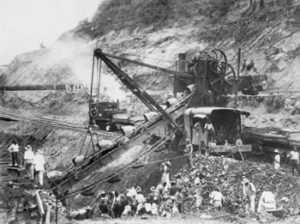

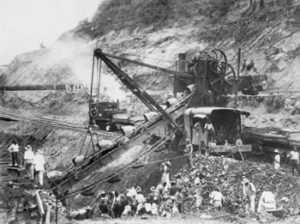

Dry excavation work was progressing in Culebra Cut and was expected to be finished by May 1885. However, there was growing concern about bank stability and the danger of slides. At the Atlantic and Pacific entrances, dredges worked their way inland. Machinery came from many quarters — France, the United States and Belgium. Equipment was constantly being modified and used in experimental combinations, but mostly it was too light and too small. A growing accumulation of discarded, inoperative equipment along the canal line testified to earlier mistakes.

With some 10,000 men employed, work was going well in September of 1883. The maximum force employed by the French at any one time was reached in 1884, with more than 19,000. The labor supply came from the West Indies, chiefly Jamaica.

But just as things appeared to be going well, tragedy struck the Dingler family. His daughter, Louise, died of yellow fever in January 1884. A month later Dingler’s twenty-year-old son, Jules, died of the same disease. As if that weren’t enough, the daughter’s young fiance, who had come with the family from France, contracted the disease and died also.

Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla

Dingler persevered, keeping up the pace of the work. He went back with his wife to France on business in June. They returned to the Isthmus in October, bringing with them a young, capable and energetic engineer named Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a man destined to play a pivotal role in the history of Panama and of the Panama Canal. Bunau-Varilla was assigned as division engineer in the key work of Culebra and Pacific slope construction, involving both dry excavation and dredging. Work at Culebra at this time needed a shot in the arm.

Then, terrible as it seems, tragedy struck again. Dingler’s wife died of yellow fever, just about a year after her daughter and son. A devastated Dingler stayed on the job until June, when he returned to France, never to return to the Isthmus that had taken from him so many of his loved ones.

Maurice Hutin then served as Director General for one month until forced to return to France for health reasons. The new acting Director General was 26-year-old Bunau-Varilla. Worker morale improved under Bunau-Varilla, and excavation increased along the line. Still, there was woefully inadequate equipment and work organization. Decauville handcars were doing most of the work at Culebra, on the Pacific side. Each of five excavators working on the Atlantic side could remove 300 cubic meters each day, but lack of spoil trains defeated their work.

There continued to be not enough of the right type of equipment; it was still too small and too light. And, there was a large turnover of labor. The spoil disposal system was inefficiently organized and managed, dump areas were too close to the excavation and slid back onto the channel whenever the rains came. Drainage ditches built parallel to the Canal helped, but not a lot. The deeper the excavation, the worse the slides. Making the slopes less steep by carving them back was another method of alleviating the slides, but this added to the total amount of digging required. And, while the soil slid with ease into the channel, the sticky clay consistency adhered with tenacity to shovels and often had to be scraped off. French bucket-chain excavators got caught and stopped by stones and rock.

In a move toward greater efficiency, Bunau-Varilla went back to the old scheme of large contractors, but instead of just one, hired several. Hand labor was cut considerably.

One contractor had let so many subcontracts in the western hill at the saddle that it became known as Contractors Hill. As late as July 1885, only about one-tenth of the estimated total had been excavated. Ultimately, the unresolved problem of the slides would doom the sea level canal plan to failure.

All the while, the toll in human lives was mounting, peaking in 1885. Yellow fever, which used to come in two- or three-year cycles, was now constant. Malaria, of course, continued to take even more lives than yellow fever. Because the sick avoided the hospitals whenever possible because of its reputation for propagating disease, much of the death toll was never recorded.

A new Director General, Leon Boyer, arrived in January 1886, relieving Bunau-Varilla. Soon thereafter, Bunau-Varilla, himself, contracted yellow fever, but did not die. However, greatly weakened, he went back to France to recuperate.

Boyer communicated to his superiors his conviction that, within current time and cost limits, it would be impossible to construct a sea level canal. To soften the report, he recommended the design proposed by Bunau-Varilla of a temporary lake and lock canal that could later, after it was built and functioning, be gradually deepened to sea level.

But, by May, he too was gone, another victim of yellow fever. The job of provisional director went to his assistant, Nouailhac-Pioch, until another Director General, a man by the name of Jacquier, the sixth since 1883, was appointed in July 1886, a position he held until the crash of 1888.

Such was the work in 1886, that the area of heaviest excavation, the stretch between Matachin and Culebra, appeared to be one continuous project. The French organization on the Isthmus had, although top-heavy with management, improved, and equipment was plentiful. Housing was clean and adequate, although not screened against flies and mosquitoes.

In spite of improvements, a lack of progress at Culebra was beginning to concern Parisian officials. Charles de Lesseps proposed to Bunau-Varilla the organization of a company to take on the work at Culebra, which he did in July 1886. The company was called “Artigue, Sonderegger et Cie.” after the two engineers who were the company’s technical members. Bunau-Varilla decided to take over the actual field supervision of the work himself. As American engineers would do later, he moved into quarters at Culebra Cut so he could watch the progress of the work. About six months later, the French work at Culebra Cut had reached peak activity. Twenty-six French excavators were digging and carrying the spoil to the dump site; still the Panama Railroad had not been harnessed to the effort of hauling spoil.

It was becoming increasingly clear to nearly everyone except Ferdinand de Lesseps that, under the circumstances, a sea level canal was out of the question and that only a high level lock canal had any hope of succeeding at this point. Under pressure from all sides, he stubbornly stuck to his guns, but finally agreed to consider making a change. Even then he delayed the inevitable for another nine months with the study of alternate plans.

Gustave Eiffel

In October 1887, the Superior Advisory Committee, released its report. The eminent French engineers established the possibility of building a high-level lock canal through the Isthmus of Panama. The plan would allow vessel transits while, at the same time, permitting dredging of a channel to sea level sometime in the future. It was never intended to be a permanent solution. De Lesseps finally, reluctantly, agreed. Bunau-Varilla’s idea was to create a series of pools in which floating dredges could be placed; the pools would then be connected by a series of 10 locks. The highest level of such a canal would be 170 feet. Work on the lock canal started on January 15, 1888. Gustave Eiffel, builder of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, would construct the canal locks. The waterway would have a bottom width of 61 feet.

In Gaillard Cut, where the average level had been lowered only 3 feet in 1886, was lowered 10 feet in 1887 and 20 feet in 1888, ultimately bringing the level to 235 feet at the time work was stopped.

Under Artigue, Sonderegger et Cie., work was going very well indeed. Some areas of the canal were nearly complete, the Panama Railroad was being rerouted away from the Cut, the first lock was nearly ready to begin installation and preliminary work on a dam had been started.

But suddenly there was no more money. A public subscription asked for by de Lesseps had failed. Shareholders, at their last meeting in January 1889, decided to dissolve the Compagnie Universelle, placing it under legal receivership under the direction of Joseph Brunet. An ignominious end to such a great effort. Some aspects of the work struggled on for a few months, but by May 15, 1889, all activity on the Isthmus ceased. Liquidation was not completed until 1894.

In France, popular pressure on the government regarding what was called the “Panama Affair” led to prosecution of company officials, including Ferdinand and Charles de Lesseps, who were both indicted for fraud and maladministration. Advanced age and ill health excused the senior de Lesseps from appearing in court, but both were found guilty and given 5-year prison sentences. However, the penalty was never imposed, as the statute of limitations had run out.

Charles, in a second trial for corruption, was indicted and found guilty of bribery. Months he had already spent in jail during the trials were deducted from his one-year sentence. Then, becoming seriously ill, he served the remainder of his sentence in hospital.

By this time, Ferdinand de Lesseps’ mental state was mercifully such that he knew little of what was going on, and he remained sequestered at home within the family circle. He died at age 89 on December 7, 1894. Charles lived until 1923, long enough to see the Panama Canal completed, his father’s name restored to honor and his own reputation substantially cleared.

Many reasons can be stated for the French failure, but it seems clear that the principal reason was de Lesseps’ stubbornness in insisting on and sticking to the sea level plan. But others were at fault also for not opposing him, arguing with him and encouraging him to change his mind. His own charisma turned out to be his enemy. People believed in him beyond reason.

The devotion to duty of the French in the face of the odds faced on the Isthmus is truly extraordinary, even when we remember what a different world it was then and the life span expectations entertained by most people, even those in favorable circumstances.

With the original Wyse Concession to expire in 1893, Wyse set out again for Bogota, where, he negotiated a 10-year extension. The “new” Panama Canal Company, the Compagnie Nouvelle de Canal de Panama was organized effective October 20, 1894.

With insufficient working capital, only some $12,000,000, to proceed with any significant work, the Compagnie Nouvelle entertained the hope of attracting investors who would help them to complete an Isthmian canal as a French enterprise. Initially, they had no intention of selling their rights; they wanted to make a success of the operation and perhaps be able to repay the losses of the original shareholders.

Sailing from France on December 9, 1894, the first group arrived in Panama to again pick up on excavation in Culebra Cut. There, every shovelful of dirt would count, no matter what type of Canal was ultimately decided upon, lock or sea level. By 1897, the work force would have expanded from an initial 700 to more than 4,000.

The Comité Technique, a high level technical committee, was formed by the Compagnie Nouvelle to review the studies and work — that already finished and that still ongoing — and come up with the best plan for completing the canal. The committee arrived on the Isthmus in February 1896 and went immediately, quietly and efficiently about their work of devising the best possible canal plan, which they presented on November 16, 1898.

Many aspects of the plan were similar in principle to the canal that was finally built by the Americans in 1914. It was a lock canal with two high level lakes to lift ships up and over the Continental Divide. Double locks would be 738 feet long and about 30 feet deep; one chamber of each pair would be 82 feet wide, the other 59. There would be eight sets of locks, two at Bohio Soldado and two at Obispo on the Atlantic side; one at Paraiso, two at Pedro Miguel, and one at Miraflores on the Pacific. Artificial lakes would be formed by damming the Chagres River at Bohio and Alhajuela, providing both flood control and electric power.

If directors of the Compagnie Nouvelle still entertained the idea that the canal could somehow be completed, they were soon faced with the reality of the situation; during and following the bitter scandal of the old company, the public had lost all faith in the project. There would be, therefore, no funds forthcoming from a bond issue, and none was tried, nor did the French government have any support for the project.

With half its original capital gone by 1898, the company had few choices — abandon the project or sell it. Company directors decided to proffer a deal to the most likely taker, the United States of America. It was no secret that the United States was interested in an Isthmian canal. With the technical commission report and a tentative rights transfer proposal in hand, company officials headed for the United States, where they were received by President William McKinley on December 2, 1899. The deal was five years in the making, but was eventually signed.

Some say that a large part of the eventual success on the part of the United States in building a canal at Panama came from avoiding the mistakes of the French. The lessons learned from the French experience were certainly helpful, but the American success was considerably more than that.