The first complete Panama Canal passage by a self-propelled, oceangoing vessel took place on January 7, 1914. The Alexandre La Valley, an old French crane boat that had previously been brought from the Atlantic side now came through the Pacific locks.

With the end of construction nearing, the Canal team began to disassemble and go on to other things. Thousands of workers were laid off, townsites were abandoned and moved with hundreds of buildings disassembled or demolished. Gorgas resigned from the Canal commission to help fight pneumonia among workers in the South African gold mines, following which he was made surgeon general of the Army. Effective April 1, 1914, the Isthmian Canal Commission ceased to exist and a new administrative entity, the Canal Zone Governor, was officially established. Colonel Goethals became the first Governor of the Panama Canal, unanimously confirmed by the Senate.

Plans were made for a grand celebration to appropriately mark the official opening of the Panama Canal on August 15, 1914. A fleet of international warships was to assemble off Hampton Roads on New Year’s Day 1915, then sail to San Francisco through the Panama Canal, arriving in time for the opening of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a world’s-fair type celebration. But no such grand opening occurred. Although the Panama Pacific Exposition went on as planned, World War I forced cancellation of planned festivities at the Canal. The grand opening was a modest affair with the Canal cement boat Ancon, piloted by Captain John A. Constantine, the Canal’s first pilot, making the first official transit. There were no international dignitaries in attendance. Observing the transit from shore, Goethals followed its progress by railroad.

The Panama Canal cost Americans around $375,000,000, including the $10,000,000 paid to Panama and the $40,000,000 paid to the French company. It was the single most expensive construction project in United States history to that time. Fortifications cost extra, about $12,000,000.

Amazingly, unlike any other such project on record, the American canal had cost less in dollars than estimated, with the final figure some $23,000,000 below the 1907 estimate, in spite of landslides and a design change to a wider canal.

Even more amazing is that this huge, complex and unprecedented project was carried out without any of the scandal or corruption that often plagues such efforts, nor has any hint of scandal ever come to light in subsequent years.

There was, of course, also a cost in lives. According to hospital records, 5,609 lives were lost from disease and accidents during the American construction era. Adding the deaths during the French era would likely bring the total deaths to some 25,000 based on an estimate by Gorgas. However, the true number will never be known, since the French only recorded the deaths that occurred in hospital.

By July 1, 1914, a total of 238,845,587 cubic yards had been excavated during the American construction era. Together with some 30,000,000 cubic yards excavated by the French, this gives a total of around 268,000,000 cubic yards, or more than four times the volume originally estimated for de Lesseps’ sea level canal.

Roosevelt is widely given credit for building the Panama Canal, and he likely never disputed the claim. However, of the three presidents whose terms coincided with Canal construction – Roosevelt, Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson – it was Taft who provided the most active, hands-on participation over the longest period. Taft visited Panama five times as Roosevelt’s Secretary of War and made two more trips while President. He also hired John Stevens and, when Stevens resigned, recommended Goethals. When Taft replaced Roosevelt in the White House in 1909, canal construction was only at the halfway mark. Goethals, however, was to write, “The real builder of the Panama Canal was Theodore Roosevelt.”

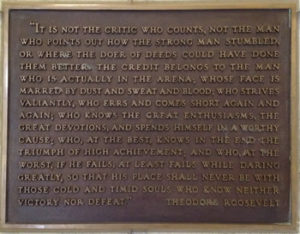

The following words of Theodore Roosevelt are engraved in a plaque on display in the Rotunda of the Administration Building, and more than anything else convey his personal philosophy and the spirit of his thinking about the achievement at Panama:

“It is not the critic who counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly, who errs and comes short again and again; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement; and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.”

David McCullough in his book “The Path Between the Seas,” wrote: “The creation of a water passage across Panama was one of the supreme human achievements of all time, the culmination of a heroic dream of over four hundred years and of more than twenty years of phenomenal effort and sacrifice. The fifty miles between the oceans were among the hardest ever won by human effort and ingenuity, and no statistics on tonnage or tolls can begin to convey the grandeur of what was accomplished. Primarily the canal is an expression of that old and noble desire to bridge the divide, to bring people together. It is a work of civilization.”